Time to call it quits on changing the world

Reality and an economic downturn have brought us back to earth

Once upon a time in December 2021, a new startup from a lauded and successful serial entrepreneur tried to completely change how people eat with a new model. Wonder, which I’ve previously referred to as the startup that makes you dinner in a van outside, paid top dollar for concepts and recipes developed by famous chefs and restaurants. Operating in just a few wealthy New York City suburbs, Wonder’s employees manned a fleet of custom kitchen vans that arrived curbside to prep customer meals and deliver it hot and fresh to their front doors.

It was an ambitious idea, backed by close to a billion dollars in capital, including a reported December 2021 $500 million from investors. It was new! Different! Game-changing! …until it wasn’t. In early February, Wonder conceded it was ditching the vans in favor of a model we’ve seen before: vertically integrated ghost kitchens in Manhattan. (In this context, vertically integrated means one company handles the cooking and distribution of the food.)

"The trucks were working well," Wonder founder and CEO Marc Lore told Insider, before explaining the company’s pivot to something that can grow faster. "We just found a better way to offer a higher quality customer experience and at the same time make a better profit margin.”

But a smattering of ghost kitchens preparing meals from a few handfuls of concepts is remarkably less innovative, even with a star-studded roster of chefs. Now, people are rejecting the undesirable costs of the so-called innovation that wants to change the way we eat. In Wonder’s case, some residents complained about noisy vans idling in otherwise idyllic neighborhoods. In other cases, pandemic-era demand has waned. Right now, incremental change is better business.

Most big technology companies of a certain era set out to fundamentally change how the world does something.

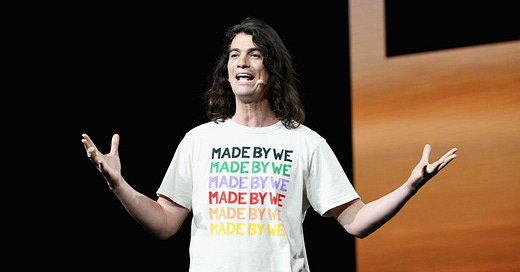

It was the kind of big-picture thinking that landed billions of dollars in backing. Remember how WeWork was meant to “elevate the world’s consciousness” in what has become one of the most publicized, ridiculed, and watched flame-outs of all time? While the circumstances surrounding that debacle were at an extreme end of… ambition, anyone who’s spent more than a few minutes around tech and startup culture can recognize the power and allure of a lofty goal.

The last year or so of cold, hard reality seems to have changed this. In 2022, global venture funding dropped by 35 percent. Companies laid off thousands — 260,000 by one count — in the name of chasing profitability and streamlining operations. The playbook that once worked so well in their favor had changed, and we all came face-to-face with a completely different environment; one that prioritizes what’s actually happening instead of dreaming big.

In the world of tech and startups, sometimes questioning a company’s ambition to change the world makes you a wet blanket.

Outsiders, including journalists, who challenge or disagree with this perceived foresight are called unfair critics, uninformed trolls, or worse. They’ve been challenged on the biggest stages. It’s happened (on a much smaller scale) to me.

Over the last year, this vibe has shifted in restaurant tech. Honesty is rewarded, transparency is featured, reality is acknowledged. When online ordering company ChowNow laid off 20 percent of its staff last year, its CEO Chris Webb admitted, “We, like everyone else, have benefited from cheap capital for a decade. And if we’re gonna go from 0 percent interest rates to 10 percent interest rates like the 1980s, all of a sudden capital got a whole lot more expensive.”

A few weeks later, Lunchbox founder and CEO Nabeel Alamgir echoed this sentiment. "We are all drunk on VC capital, and we needed to sober up," he said, after the company laid off a third of its staff.

When DoorDash laid off over 1,000 employees last November, CEO Tony Xu penned a lengthy email to employees, then made it public. He explained, “We were not as rigorous as we should have been in managing our team growth. That’s on me. As a result, operating expenses grew quickly.”

And, way back in May 2022, Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi seemed to predict all of this when he warned employees of a coming “seismic shift” in the business. “In times of uncertainty, investors look for safety.” He continued: “...while investors don’t run the company, they do own the company — and they’ve entrusted us with running it well.”

There’s something almost humbling about this, and from where I sit, it’s giving somewhat uncharacteristic “we’re all in this together” vibes. What does this mean for the future?

In December,

I argued in Bon Appetit that some of these layoffs were also a sign that some tech companies fundamentally didn’t understand how we eat. Their imagined future was kind to their business models, but reality proved the visions too ambitious. We’ve already seen how other industries have struggled to adapt after pandemic-era changes thought to be permanent have unwound themselves. The same has happened in restaurant delivery, and will probably happen in other areas of restaurant tech, too.

Maybe others, like me, have long been troubled by the particular type of overinflated, borderline self-righteous language of startups. Maybe others, like me, define themselves as hopeful pragmatists, excited by the idea of useful technological solutions to real problems, but skeptical of headline-grabbing big ideas that never really come to pass.

There are some early signals of increasing opportunity and innovation ahead. Wired notes that thanks to severance and savings, many of those employees might consider starting their own thing. One popular startup incubator said applications were up over 20 percent last year, with a fivefold increase in late applications filed in January 2023. Plus:

For investors, a solid startup can prove a better bet than tumbling stocks in harsh economic conditions. They’re agile and have fewer costs. And getting customers to pay for a new product during a recession can send a strong message that the idea has legs.

We’ve landed in the put-up-or-shut-up era. Now, the viable path forward is using technology to augment the future of hospitality without needing to change the world in the process.

What else?

Want your deliveries to arrive faster? Maybe we need to disrupt existing street addresses! (Really.)

Loved this piece about food influencers in Washington, D.C. from Jessica Sidman in the Washingtonian, but really love the debate that follows as influencers claim a journalist covering their work is a conflict of interest.

Uber’s new iPhone app offers personalization to users, including Uber Eats customers. “We’re redefining what it means, as a verb, to Uber. It can mean getting a ride or getting dinner or getting flowers or pet food delivered. It means something different to everyone,” Uber’s head of product for rides said.

Subscriptions, including restaurant subscriptions, are still working. The average person now has over 6 subscriptions (across the board, not just restaurants).

DoorDash has a new reporting API for restaurants, which should make it easier to access data about their sales in ways that make the most sense. It includes early integrations with ItsaCheckmate and Nextbite.

Olo, the company that was massively early to digital ordering and now quietly hums along as huge restaurant group after huge restaurant group adopts its ordering tech. Its latest move is a push into drive-thru and in-restaurant sales in an effort to own restaurant ordering.

OpenTable’s parent company, Booking Holdings, is sitting on $12.2 billion in cash. Oh heyyyy.